Pearson Pilings teams up with Mass Audubon’s South Coast Osprey Project to provide an all-composite platform for osprey nests

Westport, MA

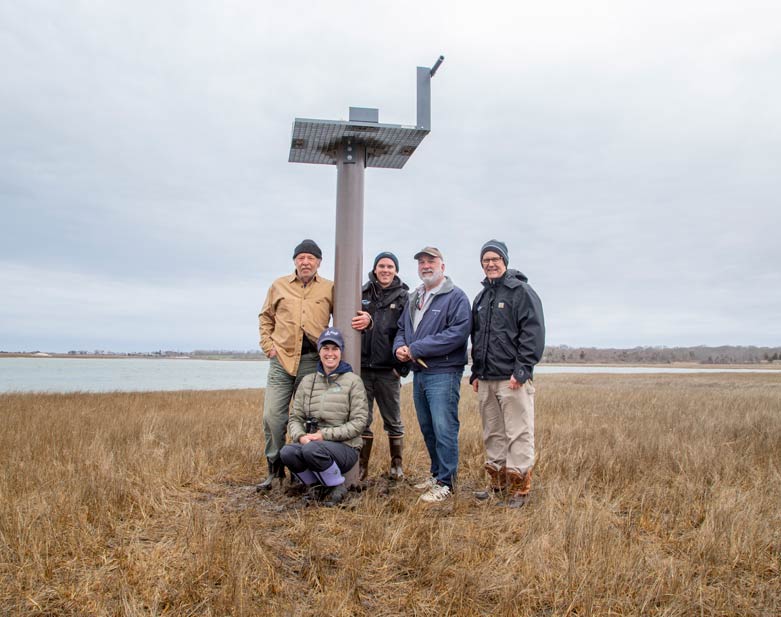

Another nesting pair of osprey was able to make its home in the marshes of Allens Pond Wildlife Sanctuary, Westport, MA thanks to a unique, all-composite nesting platform provided by Pearson Pilings. Pearson donated the platform to the Massachusetts Audubon’s South Coast Osprey Project and two other southeastern New England conservancy groups, Rhode Island’s Barrington Land Trust and the Conservation Commission of Warren.

The Osprey Project of the Massachusetts Audubon Society helps protect osprey and their habitat. With nearly 100 nests and more than 90 nesting pairs of Osprey within the program’s purview, volunteers monitor the nesting habits of the adults and the development of the chicks from egg to fledgling. Pearson donated the platform and helped with installation to support the project’s mission of monitoring osprey, maintaining nesting platforms, promoting environmental issues and engaging volunteers.

A Safer Home for Generations

Pearson Pilings’ new all-composite Osprey Pad integrates with their signature fiberglass piling to create a long lasting, non-polluting alternative to a typical wooden structure. A single piece of molded fiberglass grating forms the horizontal nesting surface, with angled sides for nest stability. Held securely in place with bolted brackets and locking hardware, the platform resists wind and weather damage. An optional perch mounts to a corner and rises 17-inches above the platform.

Pearson Pilings, Built to Last

Like all of Pearson’s products, the all-composite Pearson Osprey Pad won’t rust, rot or corrode. So the platform installed in Allens Pond will last for generations of osprey families, without the risk of leaching from pressure-treated wood. “From a bird stand point, placing platforms in a non-forested area affords a better view of incoming predators,” explains Gina Purtell, Sanctuary Director, Mass Audubon’s South Coast Sanctuaries. Luckily Pearson Pilings can be installed in environmentally sensitive marshland with minimal disruption. And the fiberglass piling repels “mammalian predators” which Purtell explains would include “raccoon, possum, snakes, mink, any arboreal tree-climbing fisher.”

Nest with the Best

When the ospreys are ready to nest the male collects nesting material, such as sticks, bark, moss, even flotsam and jetsam, which the female then arranges. Since ospreys nest on high naturally occurring platforms and between branches, on treetops or on cliffs, they acclimate well to artificial platforms. And these platforms will remain in use for decades. While they start out small in a pair’s first season, after generations of accumulation, the nests can grow to be ten-feet deep and six-feet in diameter.

Ospreys Flying High Again

Over the last four decades, the osprey population in the northeast of the United States has risen from precarious lows due to pesticide use and loss of habitat, to today’s robust level. While researchers made the connection that pesticides such as Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) were causing thinned shells and non-viable offspring, citizen scientists built osprey nest platforms to help encourage repopulation and monitor the species. These “osprey gardens” of artificial platforms rising from the marsh were responsible for helping support and monitor the osprey resurgence after legislation limited DDT use in the affected areas.

Going with the Flow

How did the species make such a dramatic recovery? Gina Purtell of Massachusetts Audubon says that their ability to adapt is key is coexisting with humans. “Osprey are really good generalists,” she explains. “If there’s a polluted body of water, they will just go a different way. If the herring dry up they will just find another type of fish.”

This same flexibility allows tracking of the osprey population to reveal patterns in climate change, sea-level and fish populations. “Whatever is abundant, that’s what they are going to fish,” says Purtell. So keeping an eye on what’s in an osprey’s mouth can reveal clues to larger environmental trends.

Pearson Joins the Fight for Osprey

The team at the Osprey Project contains only a few employees. “All the rest are volunteers,” motivated, says Purtell, by the desire to “participate in the stewardship of an animal we have a large impact on.”

For Pearson Pilings President Mark Pearson, partnering with the Massachusetts Audubon was a perfect fit. “Our mission has always been to provide minimally invasive, longer lasting alternatives to traditional materials like wood,” explains Mark Pearson. “As a life-long resident of southern New England, I value the beauty and diversity of our coastal habitats.”

From their striking appearance to their dramatic rescue from endangerment, ospreys captivate those they encounter. Interested in attracting your own nesting pair?

Since our team is mostly volunteers, the efforts of supporters like Pearson Pilings can make a huge difference in the Osprey Project and the osprey families across New England.—Gina Purtell, Sanctuary Director, Mass Audubon's South Coast Sanctuaries